A Report of Panel I discussion of the March 19th event "How Do Companies in the Greater China Region Fare in the U.S. Patent System?"

by Randy Wu

Companies in the Greater China region have long recognized that their patent strategies are critical to their success in U.S. markets. While Chinese companies have made great strides in recent years to cope with the U.S. patent system, its costs and complexities remain daunting. To focus the discussion on this important issue, on March 19, 2014, CALOBA sponsored a seminar entitled “How Do Companies in the Greater China Region Fare in the U.S. Patent System?” The event was held in the Menlo Park office of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP, which jointly sponsored the event.

The first of two panels aimed to illuminate the experiences of Chinese companies in patent litigation. The panel featured an impressive array of law firm and in-house counsel: Yitai Hu (Partner, Alston & Bird), Jacy Lee (General Counsel, Amtran), Jim Wang (Chief Legal Representative, ZTE (USA)), Xiang Wang (Asia Managing Partner, Orrick). Roger Shang, Alibaba’s Chief Patent and Technology Counsel (and CALOBA’s own board member), moderated the panel.

Empirical Patent Litigation Trends

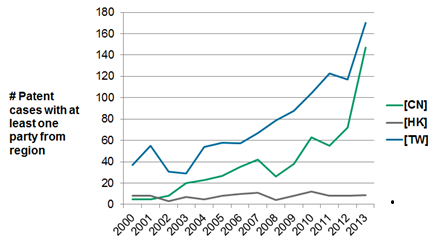

To kick off the panel, I presented highlights of an empirical study on Chinese patent litigation in the U.S. that I began at Stanford Law School. After several years of effort, I compiled a robust database of 1787 district court patent infringement cases filed between 2000 and 2013 involving 610 Chinese companies. The data shows that U.S. patent cases involving Chinese parties have rapidly increased in recent years, much of it due to troll activity:

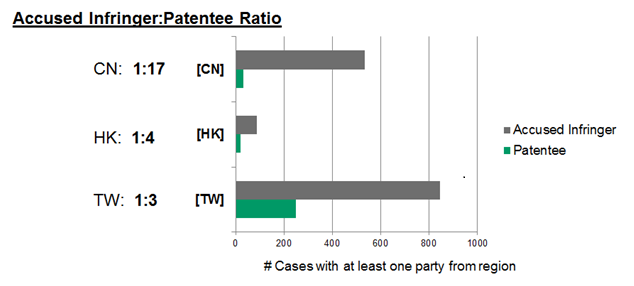

Not surprising, these increases are largely due to Chinese companies being sued, rather than Chinese companies suing. But what’s notable is that the accused infringer to patentee ratio is far more lopsided for mainland Chinese companies than for Taiwan ones:

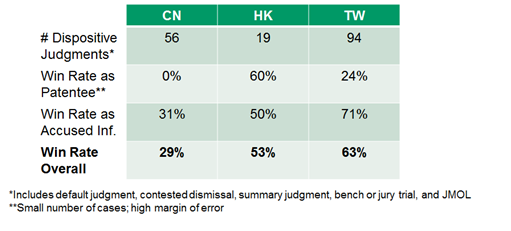

Looking at the small fraction of cases that proceed to judgment (rather than settle), Taiwanese companies also seem to do much better than mainland Chinese companies.

Notably, most of the losses for mainland Chinese companies are default judgments. Default judgments arise because of many Chinese companies’ perceptions that U.S. judgments cannot be easily enforced against them. This is a hazardous approach for companies having even occasional contacts with the U.S. For example, Zheng Liu of Orrick related an incident where a Chinese company defaulted, ignored the default judgment, only to have their assets seized when they later appeared at a U.S. trade show.

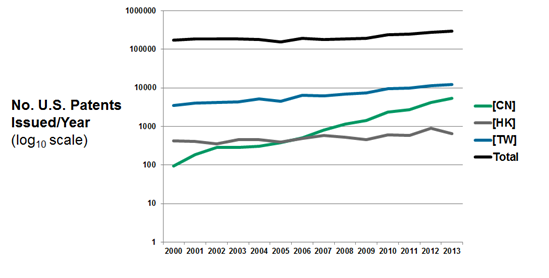

Overall, the study suggests that since Taiwan companies have had a significant head start in patent litigation, they are now more sophisticated in U.S. patent litigation than their mainland China counterparts, as evidenced by their greater rate of patent assertions, higher win rates, and lower default judgment rates. But there are signs that mainland companies are catching up, as evident by the number of U.S. patent filings:

This work is ongoing in collaboration with Peking University’s Intellectual Property School; I expect to release complete findings in late 2014.

Costs

U.S. patent litigation is notoriously expensive. A typical U.S. patent case will cost more than one million dollars, which mind-boggling sum to a Chinese company and may deter their entry into the U.S. market altogether. Ms. Jacy Lee says that even for a mature company like Amtran, patent litigation expenses can be prohibitive when it involves simultaneous litigation in multiple venues (i.e. district court and ITC). Also tricky from a cost management perspective are the unique types of costs incurred in a U.S. patent case, e.g., expert expenses. The speed of patent cases, especially ITC cases, can also create front-end expenses and discovery burdens that create huge problems for the company, says Ms. Lee.

Chinese companies who are frequently sued have tried various alternative fee arrangements to manage costs. For example, Mr. Jim Wang says that ZTE, which is sued by many patent trolls, will sometimes hire a law firm to litigate a package of several troll cases with a bulk discount. But even for patent troll cases, Jim Wang says, there is a need to balance costs with the need to do a good job. Dr. Xiang Wang added that U.S. patent litigators really should expect all of their Chinese clients to complaint about fees (the only cases in which they don’t complain about fees are industrial espionage cases because they are in jail).

Document Discovery

Chinese companies have a very hard time understanding the permissive nature of U.S. discovery, especially when they are dealing with the issues for the first time. Discovery is disruptive to the business and counsel should expect fierce push-back from Chinese executives. For example, Xiang Wang noted that Chinese companies often don’t understand the need to produce truthful documents and testimony, and sometimes may be tempted to falsify documents. Dr. Wang further mentioned that Chinese companies are usually reluctant to produce confidential documents even under a protective order. Translating documents into English from Chinese, especially high-volume documents like email, can be a massive burden, Mr. Jim Wang says. Therefore, Mr. Yitai Hu says, counsel representing Chinese companies should recognize that it will take them a long time to adapt to the mindset of U.S.-style discovery. A healthy long-term working relationship with a U.S. attorney is critical to this adaptation process.

Witness Discovery

The cultural background of a Chinese witness can have a tremendous impact on deposition and trial testimony. Mr. Hu says that Chinese witnesses usually prefer to testify in Chinese through a translator, believing that speaking in their native language will give them an advantage. This tactic can backfire, according to Mr. Hu. He gave one example of a witness who gave all testimony in Chinese on grounds that he was not competent to testify in English, but it later emerged that he attended UCLA, giving rise to implication that he was trying to hide something. Similarly, Mr. Roger Shang told an anecdote of a witness who testified in Chinese, but it later emerged that all of his email correspondence was in English. It’s difficult to rationalize these discrepancies, Mr. Shang says, by trying explaining that written fluency can be very different than oral fluency, or that it may be easier to write e-mail s in English than Chinese for reasons unrelated to fluency. American juries tend to believe that everyone speaks English, Mr. Hu says, and not playing into the stereotype can hurt you.

Dealing with Patent Trolls

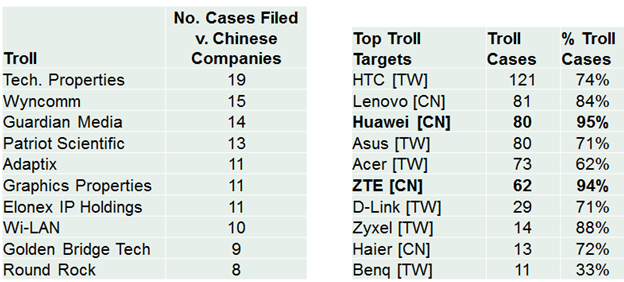

A large proportion of cases against Chinese companies are brought by patent trolls, especially in the last few years. Here is a breakdown of top trolls suing Chinese companies and their targets based on my empirical study:

According to the panelists, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to dealing with patent trolls. The strategy depends on the troll’s up-front demand: if the demand is reasonable then defendants usually settle quickly, but if the demand is high then companies have more incentive to fight. Therefore, companies tend to view troll cases as primarily a matter of cost management. But companies should also be aware of the reputations effects of being too “soft” on trolls. Some companies therefore try to take a tough stance and will avoid settling with trolls even if they have to incur large legal fees to fight them off. But this strategy may not be economically viable for companies bombarded with too many troll cases. An alternative strategy is joining a defensive aggregators such as RPX. RPX membership is expensive, however, and Huawei and ZTE are the only Chinese companies to join RPX to date.

Potential Bias

There is definitely potential bias against Chinese companies in the U.S. judicial system, according to the panelists. For example, a common jury tactic in American versus Chinese company patent cases, according to Mr. Hu, is for the American patentee to play up the notion that the Chinese company is simply copying American innovation. One way to counter this is to send the message that it is the Chinese company that is innovative, allowing them to eclipse their American rival in an efficient marketplace. This argument can be tricky to make in front of an American jury, however, Mr. Hu says.

Dr. Xiang Wang takes a broader perspective that every country will have some xenophobic biases in their judicial system, but that the U.S. system is probably one of the best in allowing foreign litigants a fair shake. Dr. Wang also points out that sometimes this bias can work in reverse: Chinese witness will automatically assume that American decision-makers will be biased, and this assumption can work in the Chinese company’s disfavor. These perceptions will not change quickly, Dr. Wang says, and will occur only when Chinese companies become more mature in their understanding of the U.S. legal system.

The Road Ahead

Overall, Chinese companies seem to follow a maturation process when it comes to U.S. patent litigation. Companies that have been sued for U.S. patent infringement will become more cognizant of the importance of patents, and will start to build up their own U.S. patent portfolios. Building their own patent arsenals, Ms. Lee says, may be one of the most effective ways for Chinese companies to control costs of litigation by building more leverage (at least in non-troll cases). The statistics show that this is precisely the strategy that Taiwan companies have taken over the past decade, and every sign shows that mainland Chinese companies are doing the same.

About the Author

Randy Wu is an associate in the intellectual property litigation group of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe and a recent graduate of Stanford Law School. He is a member of the CALOBA executive team. Contact randy.wu@gmail.com for questions.

A PDF version of this article may be found here: 2014 CALOBA IP Seminar Part I